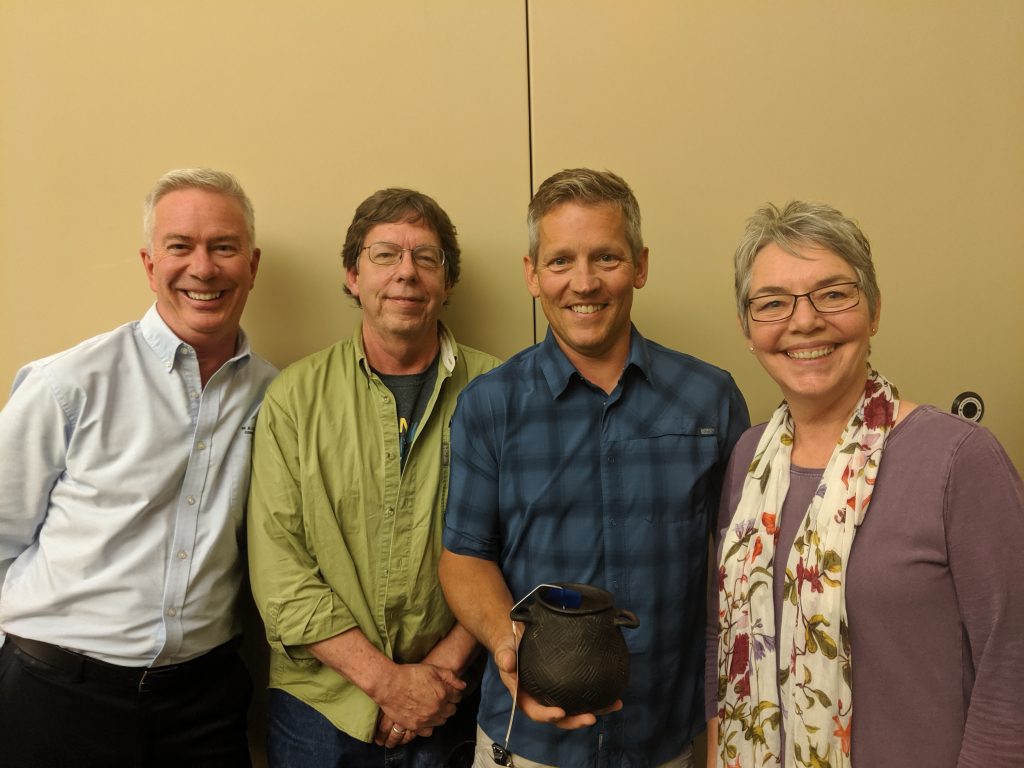

Mainspring Conservation Trust Board of Directors recognized the retirement of long-time board member Richard Clark of Franklin, at their recent board retreat. Clark has been on the board since 2002, serving as chair, vice-chair, and secretary in those 17 years. As founder and president of Clark and Company Landscape Services, he will continue to advise the nonprofit on beautification projects.